Business in the Beginning: From Jamestown to New Nation (1606 – 1790)

Business in the Beginning: From Jamestown to New Nation (1606 – 1790)

The history of business in America from 1606 to 1790 reflects the development of economic activities and institutions that laid the foundation for the modern U.S economy. This period covers the early colonial era through the American Revolution and the establishment of the new nation.

Early Colonial Period (1606-1700)

Colonial Charters and Settlements: The history of business in America began with the establishment of colonies under charters granted by the English Crown. In 1606, King James I granted charters to the Virginia Company, leading to the establishment of Jamestown in 1607. The Virginia Company and other early colonial enterprises, like the Massachusetts Bay Company, were joint-stock companies formed by investors seeking profit from resources in the New World.

Agriculture and Trade: Early colonial economies were primarily agrarian, focusing on subsistence farming. However, as settlements expanded, colonies began producing surplus crops such as tobacco in Virginia and Maryland, which became significant cash crops. Tobacco quickly became the backbone of the colonial economy and a major export to Europe.

Indentured Servitude and Slavery: To meet labor demands, colonies relied on indentured servants—people who worked for a set period in exchange for passage to America. By the late 1600s, the institution of slavery had become more entrenched, especially in Southern colonies, where plantation agriculture required a large labor force.

Fur Trade and Other Industries: In the Northern colonies, the fur trade became a significant business, particularly involving Native American interactions. Fishing, lumbering, and shipbuilding also developed as important industries, especially in New England.

Growth and Diversification (1700-1760)

Expansion of Trade Networks: The 18th century saw an expansion of trade networks. The Triangular Trade connected North America, Africa, and Europe, with colonies exporting raw materials and importing manufactured goods. The colonies also engaged in intercolonial trade, fostering economic interdependence.

Development of Colonial Industries: By the mid-1700s, colonial industries had diversified. Shipbuilding became a significant industry in New England due to abundant timber, while ironworks developed in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Local manufacturing began to emerge, although it remained limited compared to agriculture and trade.

Mercantilism and Economic Regulation: The British government maintained a mercantilist policy, regulating colonial trade to benefit the mother country. Acts like the Navigation Acts restricted colonial trade to British ships and mandated that certain goods be shipped only to England or other colonies. These regulations aimed to ensure that the colonies contributed to Britain’s wealth and power.

Pre-Revolutionary Period and American Revolution (1760-1783)

Pre-Revolutionary Period and American Revolution (1760-1783)

Economic Tensions and Taxes: Economic tensions between the colonies and Britain intensified in the 1760s as Britain sought to increase revenue from the colonies through various taxes, such as the Stamp Act (1765) and the Townshend Acts (1767). These measures were resented by colonists, who felt they lacked representation in British decision-making.

Boycotts and Domestic Production: In response to British taxes and regulations, colonists organized boycotts of British goods, leading to a rise in domestic production. Women played a crucial role in spinning cloth and other goods to reduce reliance on British imports, fostering a spirit of economic independence.

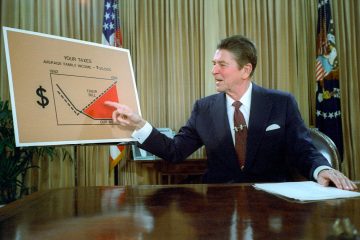

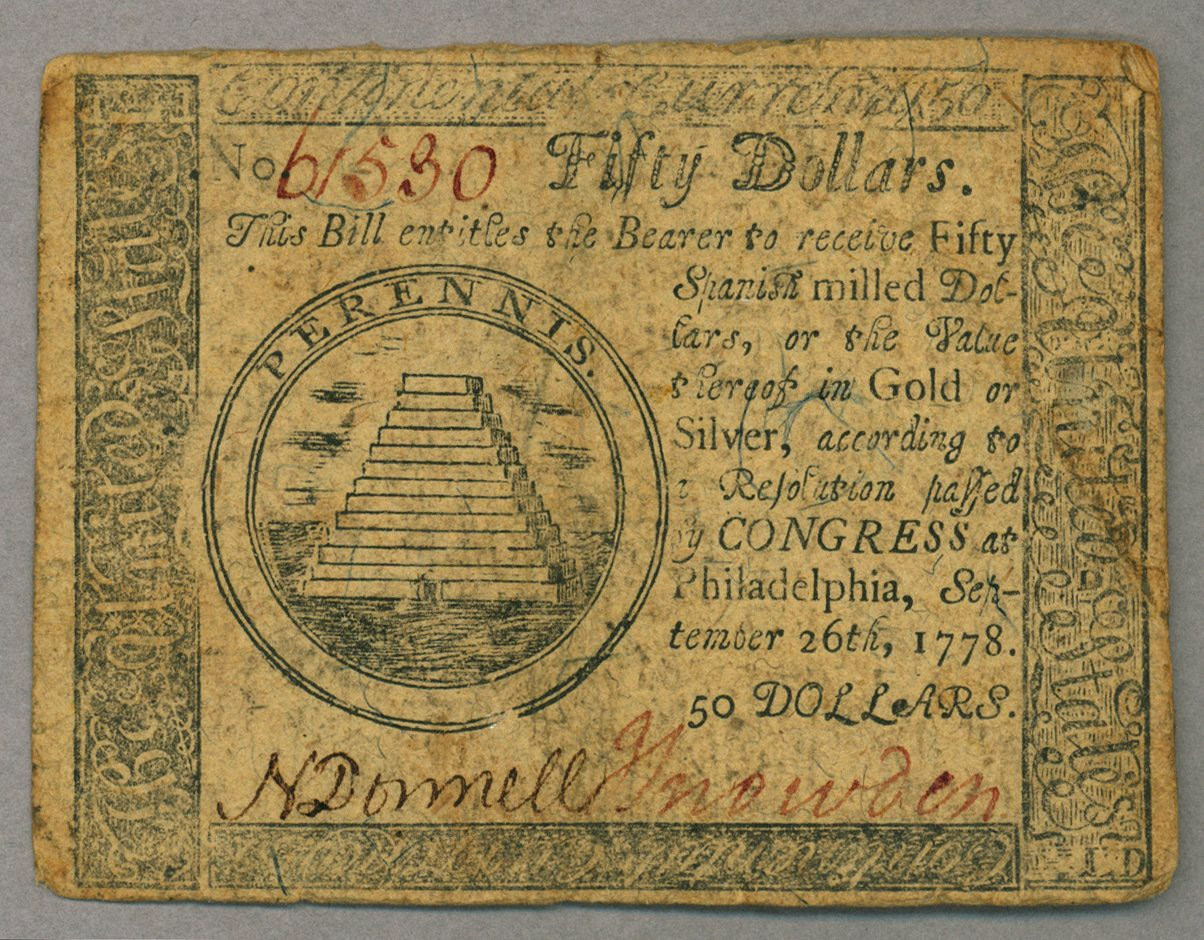

War Economy and Financing the Revolution: The American Revolution disrupted traditional economic activities, leading to a war economy. Financing the war proved challenging; the Continental Congress lacked the authority to tax and relied on loans, printing money, and foreign assistance, leading to inflation and economic instability.

Post-Revolution and Formation of a New Nation (1783-1790)

Post-War Economic Challenges: After the Revolution, the new nation faced significant economic challenges, including war debt, inflation, and a lack of a stable currency. Trade had been disrupted, and many loyalists, who had been prominent business people, left the country.

Creation of a National Economy: The Articles of Confederation, America’s first governing document, did not grant the federal government sufficient power to regulate commerce or collect taxes, leading to economic difficulties. The Constitution, ratified in 1788, provided a stronger framework for economic development, including the power to regulate commerce, collect taxes, and establish a national currency.

Beginnings of American Banking: The post-Revolution period also saw the beginnings of American banking. The Bank of North America, founded in 1781, was the first de facto central bank. Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, later proposed the creation of a national bank, which led to the establishment of the First Bank of the United States in 1791, aiming to stabilize the economy and foster economic growth.

The period from 1606 to 1790 in American history was marked by the evolution of business from early colonial ventures and trade to a more diversified economy shaped by agriculture, commerce, and emerging industries. The American Revolution and subsequent formation of a new nation brought significant economic changes, setting the stage for the growth of a national economy and laying the groundwork for future industrialization and expansion.

Main Image Source: Generative AI | Image Boston Harbor: Wikimedia Commons | Image Continental Currency: Wikimedia Commons

Content Sources: Original | Generative AI